Optimization involves【ɪnˈvɑːlvz 需要;影响;(使)参加,加入;包含;牵涉;牵连;使成为必然部分(或结果);】 configuring, tuning, and measuring performance, at several levels. Depending on your job role (developer, DBA, or a combination of both), you might optimize at the level of individual【ˌɪndɪˈvɪdʒuəl 单独的;个别的;独特的;一个人的;与众不同的;】 SQL statements, entire applications, a single database server, or multiple networked database servers. Sometimes you can be proactive【ˌproʊˈæktɪv 积极主动的;先发制人的;主动出击的;】 and plan in advance for performance, while other times you might troubleshoot a configuration or code issue after a problem occurs. Optimizing CPU and memory usage can also improve scalability【skeɪləˈbɪlɪti 可扩展性;可伸缩性;可量测性;】, allowing the database to handle more load without slowing down.

Optimization Overview

Database performance depends on several factors at the database level, such as tables, queries, and configuration settings. These software constructs result in CPU and I/O operations at the hardware level, which you must minimize and make as efficient as possible. As you work on database performance, you start by learning the high-level rules and guidelines for the software side, and measuring performance using wall-clock time. As you become an expert, you learn more about what happens internally, and start measuring things such as CPU cycles and I/O operations.

Typical users aim to get the best database performance out of their existing software and hardware configurations. Advanced users look for opportunities to improve the MySQL software itself, or develop their own storage engines and hardware appliances to expand the MySQL ecosystem【ˈiːkoʊsɪstəm 生态系统;】.

1.Optimizing at the Database Level

The most important factor in making a database application fast is its basic design:

• Are the tables structured properly? In particular, do the columns have the right data types, and does each table have the appropriate columns for the type of work? For example, applications that perform frequent updates often have many tables with few columns, while applications that analyze large amounts of data often have few tables with many columns.

• Are the right indexes in place to make queries efficient?

• Are you using the appropriate storage engine for each table, and taking advantage of the strengths and features of each storage engine you use? In particular, the choice of a transactional storage engine such as InnoDB or a nontransactional one such as MyISAM can be very important for performance and scalability【skeɪləˈbɪlɪti 可扩展性;可伸缩性;可量测性;】.

【InnoDB is the default storage engine for new tables. In practice, the advanced InnoDB performance features mean that InnoDB tables often outperform the simpler MyISAM tables, especially for a busy database.】

• Does each table use an appropriate row format? This choice also depends on the storage engine used for the table. In particular, compressed tables use less disk space and so require less disk I/O to read and write the data. Compression is available for all kinds of workloads with InnoDB tables, and for readonly MyISAM tables.

• Does the application use an appropriate locking strategy? For example, by allowing shared access when possible so that database operations can run concurrently, and requesting exclusive access when appropriate so that critical operations get top priority. Again, the choice of storage engine is significant. The InnoDB storage engine handles most locking issues without involvement from you, allowing for better concurrency in the database and reducing the amount of experimentation and tuning for your code.

• Are all memory areas used for caching sized correctly? That is, large enough to hold frequently accessed data, but not so large that they overload physical memory and cause paging. The main memory areas to configure are the InnoDB buffer pool and the MyISAM key cache.

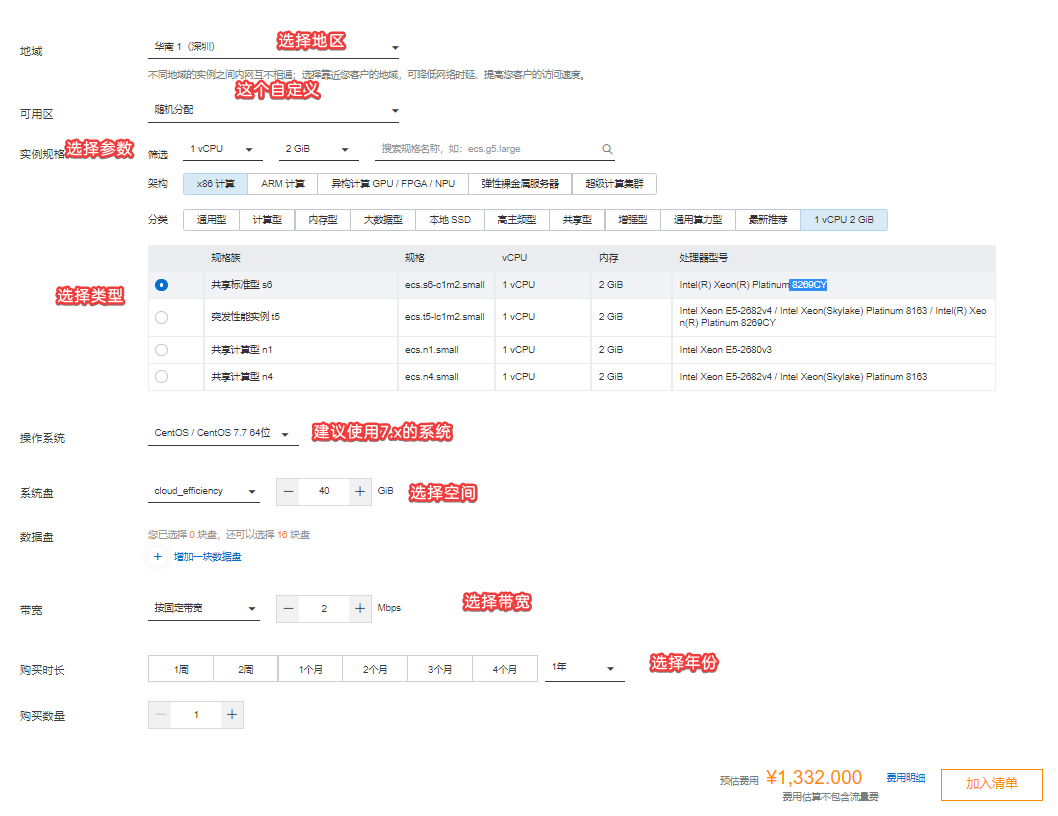

2.Optimizing at the Hardware Level

Any database application eventually hits hardware limits as the database becomes more and more busy. A DBA must evaluate whether it is possible to tune【tuːn (给收音机、电视等)调谐,调频道;调整,调节(发动机);调整;(为乐器)调音,校音;】 the application or reconfigure the server to avoid these bottlenecks【ˈbɑtəlˌnɛks (尤指工商业发展的)瓶颈,阻碍,障碍;瓶颈路段(常引起交通阻塞);】, or whether more hardware resources are required. System bottlenecks typically arise from these sources:

• Disk seeks. It takes time for the disk to find a piece of data. With modern disks, the mean time for this is usually lower than 10ms, so we can in theory do about 100 seeks a second. This time improves slowly with new disks and is very hard to optimize for a single table. The way to optimize seek time is to distribute the data onto more than one disk.

• Disk reading and writing. When the disk is at the correct position, we need to read or write the data. With modern disks, one disk delivers at least 10–20MB/s throughput. This is easier to optimize than seeks because you can read in parallel from multiple disks.

• CPU cycles. When the data is in main memory, we must process it to get our result. Having large tables compared to the amount of memory is the most common limiting factor. But with small tables, speed is usually not the problem.

• Memory bandwidth. When the CPU needs more data than can fit in the CPU cache, main memory bandwidth【ˈbændwɪdθ 带宽;频宽;带宽值,频宽值(计算机网络或互联网接口一定时间内传送信息量的量度,按每秒传送的字节数计);】 becomes a bottleneck. This is an uncommon bottleneck for most systems, but one to be aware of.

3.Balancing Portability and Performance

To use performance-oriented SQL extensions in a portable【ˈpɔːrtəbl 便携式的;手提的;轻便的;】 MySQL program, you can wrap【ræp 包;裹(礼物等);(使文字)换行;用…包裹(或包扎、覆盖等);用…缠绕(或围紧);】 MySQL-specific keywords in a statement within /*! */ comment delimiters. Other SQL servers ignore the commented keywords.